RUM HERITAGE

Barbados is widely credited as the birthplace of rum. The first commercial sugar cane crop was planted in in Barbados 1640, but settlers had already been harvesting small crops to create a popular local beverage called 'Kill-Devil' an early ancestor of the modern-day spirit. Crude distillation methods resulted in a poor-quality product described as '...a hot, hellish, and terrible liquor', yet its popularity grew.

Over the next century, distillation practices significantly improved and Barbadian rum became renowned in both Europe and Colonial America. Alcohol played a large role in 17th and 18th century life; it was drunk during social occasions, used medicinally and served as a valuable trading commodity.

The first settlers arrived in Barbados in February 1627; within 10 years over 6,000 English settlers had arrived. Initial landholdings were primarily used for tobacco and cotton; between 1631 and 1637, an additional 37,770 acres of land were handed out. America had a stronghold on the tobacco market, so planters were desperately searching for another prosperous crop.

When Dutch Jews immigrated to the island from Suriname, they brought with them the equipment, expertise and trade routes to establish a sugar industry, as well as the financing necessary to sustain the island's fledgling economy until the first sugar crop was ready for harvest.

Benjamin Berringer and John Yeamans, collectively owning over 360 acres of land in the island's highlands, enjoyed early success as planters. They burned the brushland to create arable fields; while some land would have been retained for provisional crops, the majority of land on the plantations would have been dedicated to sugar cane.

For several decades, Barbados enjoyed an economic boon; however natural disasters, political unrest, stringent English rule and an increased world supply of tropical products led to declining profits from 1661. It was during this time that John Yeamans and other Barbadians migrated to American Colony known as Carolina in search of greater and more secured prosperity.

Those who remained in Barbados struggled through years of fire, periods of drought and excessive rain, as well as a smallpox epidemic that drastically affected the island's slave population. The depression stretched into the 1700s; to survive, Barbadians participated in both legal and illegal activities to supplement their income. Through struggle and strife the islanders persisted; a survey taken between 1717 and 1721 listed 870 estates and 320 windmills used for sugar production. It is this survey that documents that St. Nicholas Abbey, then known as Dottin Plantation, had adopted windmill-driven production by this time.

The settlers’ persistence paid off in 1739, when a new Sugar Act passed providing for direct trade with Europe, leading to a sharp rise in sugar prices. A planter aristocracy established, paving the way for the large plantations that would carry the Barbadian economy through the next century.

Despite the political and economic advancements, plantations continued to encounter difficulties, and there was even a temporary shift to cotton in the late 1700s as it did not require expensive preparation and left more arable land available for growing provisions. A second Sugar and Molasses Act boosted sugar trade, but it was still a very difficult time for many plantations, St. Nicholas Abbey included.

It was during this time that the Nicholas Family sold the Plantation to Joseph Dottin, who gifted the property to his daughter, Christian, and her husband, Sir John Gay Alleyne, on their wedding day in October 1746. Sir John is credited with introducing both the production of molasses, a thick dark-brown by-product of sugar production used in baking, as well as rum, a spirit created by fermenting the molasses.

Sir John, who successfully managed the Mount Gilboa Plantation and Distillery for his friend, John Sober, introduced the same rum distillation methods to St. Nicholas Abbey in the 1750s, which were much more sophisticated than those used by the first settlers. Barbados enjoyed a prosperous rum trade with the American colonies for some time, helping to boost the island's economy, and the plantation also profited from this new line of trade.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, Barbadian slaves were treated harshly; however growing agitation in England over the colonial practice led planters to improve their treatment. Slaves were provided with thatched roof huts, clothing and food allowances; working hours were reduced to daylight hours only with Sundays and holidays off. In 1805, Barbados amended its laws to classify the killing of a slave as murder, and in 1807, England passed the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act.

The Great Hurricane of 1831, thought to be the most devastating in the island's history, brought financial support that aided a period of change and economic growth in Barbados. England sent hurricane relief funds to help the colonists rebuild, and temporarily lifted customs duties. The plantation owners received further compensation when England passed the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833. In 1834, slaves were classified as apprentices, and in 1838, they were granted their freedom.

Although the Slavery Abolition Act led to a decline in sugar production throughout most of the Caribbean, Barbados experienced an increase in production, strengthening its role in international trade. This growth was buoyed by several factors; most significantly the agreement plantation owners made with the newly freed labourers - in exchange for a small plot of land and the plantation’s support in harvesting and transporting their crops, the free labourers would work for the plantation during harvest time.

The island’s economic stability was further buoyed by the permanent white population’s commitment to maintaining the sugar industry as part of their heritage. They organised an agricultural society that experimented with methods of increasing production while minimising costs; subsequently Barbadian plantations reaped some of the greatest profits in the region.

St. Nicholas Abbey’s ongoing archaeological program, managed by the College of William and Mary, places special focus on artifacts related to slave life on the plantation. The Warrens plan to restore part of the plantation as an educational centre for visitors to learn more about this period in history, and its significant contribution to our present. The centre will feature archeological findings and eudcational displays.

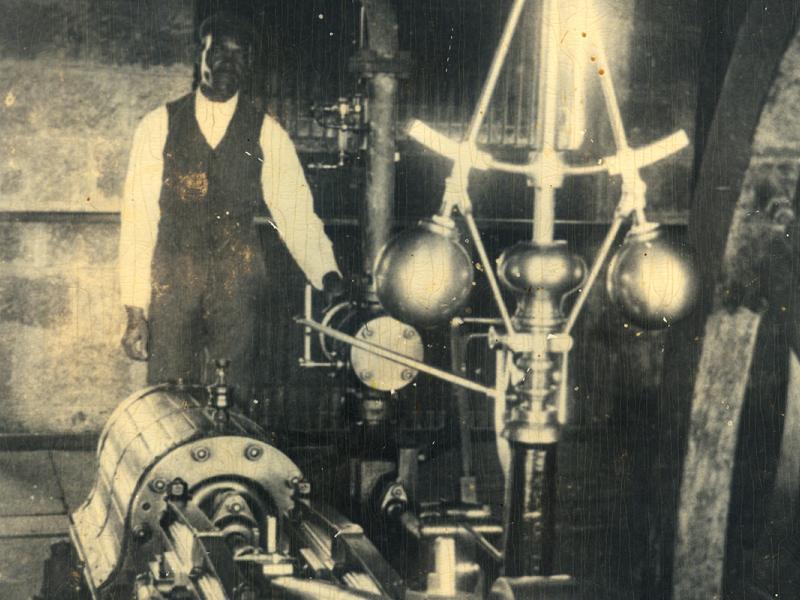

In the late 1800s, steam power was introduced to the local sugar industry; the steam mill could extract more juice from the sugar cane, increasing production by 10-15% over the traditional windmills. St. Nicholas Abbey installed a steam engine in 1890; built by Fletchers of Derby in London, it helped the plantation become one of the most successful on the island.

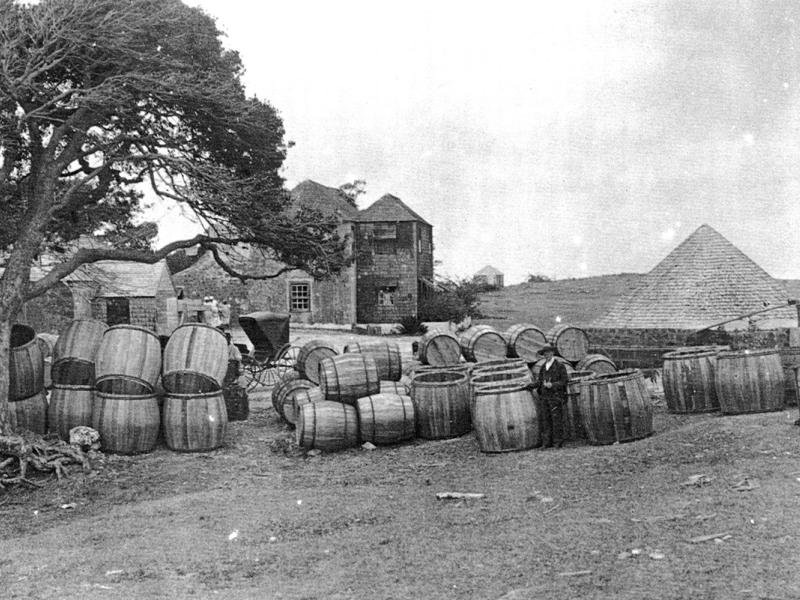

Over time, however, competition from other sugar and rum producing regions (including the United States) made it increasingly difficult for Barbadian sugar plantations to sustain profitability, and St. Nicholas Abbey was no exception. The Plantation ceased operations in 1947; the mill and equipment were sold as scrap.

In 1983 a similar steam mill was brought to St. Nicholas Abbey by a venture between the Canadian High Commission and Col. Cave, who had a vision to restore the mill as a visitor attraction. The Barbados National Trust aided the project by serving as trustees for the grant; Col. Cave managed the entire project and facilitated the preservation of the steam mill, which was the last of its kind in Barbados. The present owners saw Col. Cave's vision through and had the mill restored and re-commissioned in 2006; it is now used to grind sugar cane for St. Nicholas Abbey’s rum production, which visitors can see during seasonal operation. Parts of a similar mill originating from nearby Mt Prospect Plantation are on display on the lawn; kindly donated by the Corbin Family.

*Information on this page obtained from BARBADOS: THE SUGAR STORY, by Geoffrey Badley (Publisher: Herbert Publishing)